I was at a Christmas party in conversation with a local Timken engineer who, hearing I design food forests, wanted to pick my brain on apple trees. He had six trees in two rows of three, well spaced in his backyard. He was throwing out terms about the mainstream organic sprays he was using, and framed his questions expecting me to know some super organic spray, or spray regimen, that would fix his problems of pests and low vigor in general. I don’t think he expected the answer I gave: ‘What’s planted around the trees?’

We often think of the rules of spacing as rules for keeping other plants away from each other. In practice I find the lines blur between species, and enters a much more broad science: it’s what should be included near the plant, as well as what shouldn’t. Between these two aspects, you make or break the majority of fruit tree problems.

The lines often blur between species because, let’s face it, plants don’t grow in a vacuum and always have something growing up against them. In this guy’s case, his trees were planted right into his lawn. They were in competition with the grass.

Looking at their history, grass and trees are in most cases nemesis of one another. Trees make forest; but grass needs open space. The setting in most yards of trees with grass between is quite artificial, and only exists because we keep the grass mowed. In any other situation, trees would take over.

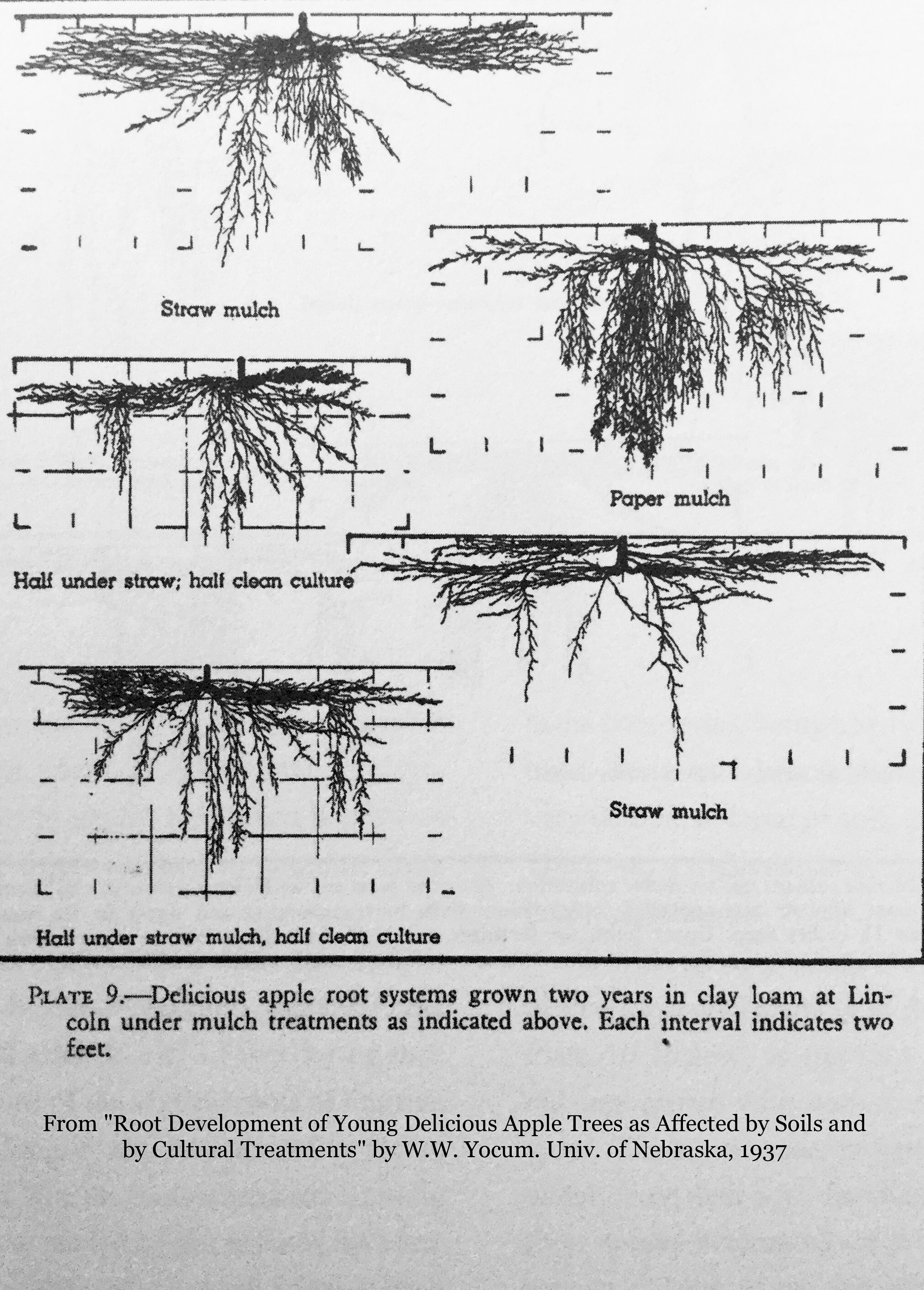

The prairies are the kingdom of grass, and these occured because of rain shadows, or areas where circumstances such as the Rocky Mountain range messed with the winds that carry rain, creating droughts in one part of the year, and near flooding in another. Trees don’t like that, because most have relatively shallow roots, as much as 80 percent residing in the top three feet of soil depending on the kind and its conditions; but prairie plants, such as the grasses, and N fixers like senna hebecarpa, put roots down unusually deep, so reach the water table whether rain comes or not.

Have you ever wondered as you pass woods how the trees survive so close? If you were planting an oak tree in your yard that would someday reach a hundred foot tall, can you imagine the spacing recommendations? They would be over fifty feet apart. Most yards couldn’t fit more than one tree. But in the woods they stand on top of each other, growing for hundreds of years, happy, and healthy.

Studies have shown that trees can grow their roots deep into the ground, but prefer to keep their roots higher in the soil if possible. There is more organic matter, hence nutrients and water, in this layer. If there isn’t, trees will try to put in the work to grow deeper. This is a lot more work, and certainly isn’t their first choice.

What trees really prefer is building networks in which they share and preserve resources. For instance, trees have what is called hydraulic redistibution, which is a fancy term for moving water not only up for their own use, but back down into the soil for storage, and horizontally to other plants. Peter Wholleben, in his book The Hidden Life of Trees recalls his surprise when he found a ring of roots from a beech tree that must have been cut down well over a century beforehand, but still had green, living roots showing above ground. It had no leaves, and the stump was gone. As he explained, citing various studies, the living trees around this ancient (should be dead) tree were feeding it sugars made in their leaves, keeping it alive. Likely, they got some kind of kickback from the extended root system because it allowed them access to more resources.

This is in ancient, established forests, so conditions aren’t quite the same for our young transplants. We can get some similar effects by growing fruit trees in more open settings, or riparian zones. These are zones similar to fencerows and overgrown fields where grasses are just converting to trees. These zones are iconically untidy and wild; but skillful gardeners know the elements of these zones, like clay in a potters hand, have the best potential to form the most beautiful, lush gardens.

Riparian zones have many layers, with notably high numbers of low growing herbaceous and woody shrubs, many of which are nitrogen fixers. The quickest way to simulate this ecology is making ‘guilds’ of plants right around your fruit trees. Here is my manual of bed building for info on quickly clearing grass without tillage. Plan on expanding these plantings every year until the beds around your trees meet. If the tree is older, and larger, the bed should extend at least a couple feet beyond its drip line.

Any guild should include at least 2 woody nitrogen fixing plants, about 5 plants that do not fix nitrogen but can be cut for mulch, such as comfrey, or a groundcover of something like mint, then several fruiting shrubs like raspberry or honeyberry, and some perennial vegetables.

This is the best method if you already have fruit trees in the ground, like our engineer friend. If you’re just planning your food forest, Robert Hart, the father of the northern food forests, recommended planting full size or standard fruit trees at recommended spacing for their size, in rows like any orchard, but then semi standard or medium trees, then dwarf trees, then shrubs, then herbaceous plants, then vines to climb and fill in the cracks between them.

I’d recommend mulching as much as you can, and planting that area with a complete planting like this. The space should be completly filled with plants, and will establish faster with less work overall.

This system gives quite attractive results that are increasingly less cost and labor than serial applications of even organic, clay-based sprays, pyrethrums and neems, let alone the more harsh chemicals. There is work later on, but this is of course dabatable, because its mostly harvests of fruit. Sounds like pleasant work to me.

Funny you should mention mulching…I’m just rereading your PASSIVE Gardening book, trying to get things firmly fixed in my head before our active planting season starts. I’m having one of my occasional big planting years when a few new fruit trees and scads of new berries will be going in, so I will be mulching with leaves and purchased straw at first, but hope to be planting mulching plants into the straw as I can afford them, and I’m trying to get some new areas planted in alfalfa.

I was hoping to get started with Amorpha but Oikos still shows everything I really want as “out of stock.” I hope a new catalog comes out soon.

Happy growing season. Just the few things that I’m harvesting so far make me deliriously happy.

LikeLike

Happy growing season to you too! We are actually experiencing some very unusual warm weather here, so it actually feels quite like spring. I was quite pleased to get some lovely cooking greens from our greenhouse the other day.

Prairie Moon Nursery also carries Amorpha fruticosa, although bare root. http://www.prairiemoon.com/seeds/trees-shrubs-vines/amorpha-fruticosa-false-indigo.html

Intensely interested in how the PASSIVE system development goes for you. With your excellent grasp of the concepts, I think you’ll see surprisingly good results.

LikeLike

Very nice Presentation

LikeLike

Thank you! I appreciate you taking the time to comment.

LikeLike

Yes, grass is the enemy of trees.

Unfortunately, I have another problem in that there is a hard pan of clay under my thin layer of soil, so no doubt the roots struggle a bit. However, all trees in my garden withstood the recent harsh winds, so they must have reasonable anchors.

LikeLike

Thus we see the benefit of many plants providing wind protection for one another. It’s amazing what so many tiny roots can do to hold a large tree in the ground I guess. The denuded bay plant sounds pretty serious though.

It’s a surprising amount of electrical chemistry that makes hardpan so hard to breach. Increased Calcium is one component that might help reduce its strength. This will also come with increased organic matter too. You might find this post of interest: https://mortaltree.blog/2016/03/04/the-best-fertility-enhancer/

LikeLike

I’ll take a look at your recommended post. Out of interest, will the organic matter move down into the hard pan of clay, it being the subsoil.

As for the denuded bay, that was I think because of bamboo canes repeatedly hitting it, so no amount of fertility or vegetation could have protected it… the canes have now moved to the shed, so at least that won’t be happening again 😃.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh …. well yes, being beaten by canes certainly would do it. Thanks for informing me.

There are several ways organic matter moves down through the soil: passive percolation, active soil life (like worms) working their way up and down, and plants growing deep roots. Taproot radish is a classic, although long term, method of getting organic matter in the soil. The other way is just cutting into the soil to jumpstart the process, as the post explains.

LikeLike

Unfortunately, the cutting method is a bit too late for me as most of the garden is covered in hugel beds now and of course I wouldn’t want to remove the trees. However, I did dig into the subsoil as best I could whenever I exposed it – even when I knew very little about any gardening matters, it simply made sense to try to open up that clay subsoil.

I guess dandelions could do the same job as the taproot radish?

LikeLike

Certainly. I have a book (the same one I got the tree root picture from) showing pictures of excavated dandelion roots that reach 4.5 feet deep. It doesn’t mention what kind of soil it was in; but I think it’s safe to say dandelions have the potential to grow very deep.

LikeLike

That is what I understood, too. I haven’t seen any evidence in my garden of them penetrating to clay pan but you never know.

Anyway, part of the reason for the hugel beds is to increase the ‘soil’ depth, so that perennial plants can get a better foothold. As it’s still early days, and I’ve got a lot more planting to do, we shall see how it all unfolds.

Thanks for your responses to my queries, Luke.

LikeLike

Thank you for this fascinating post Luke. I have already looked up The Hidden Life of Trees to order a copy in a minute. I am also sending a link to this post immediately to forest gardening friends here in the UK!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Why thank you Anni! I hope your friends find it of interest too. The Hidden Life of Trees was an extremely fascinating book with a lot more suggested applications for agriculture than what I was able to mention in this post. I will be posting another like this one soon. Thanks again.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Anni's perennial veggies and commented:

From one of my favourite bloggers – Luke Simon – who blogs asn ‘Mortal Tree’ – a fascinating and informative post about how trees grow. I am going to order the book he recommends right now as it looks amazing.

LikeLike

As per my accidental comment on your Manual of Bed Building post from 2015, thanks for this!

LikeLiked by 1 person

As per my reply under Manual of bedbuilding:

It seems you’ve read a permaculture textbook or two. Thanks for the comment. I drew the guild using pencil and watercolor brush in Adobe Sketch. Great app that’s free if you want to find it on the App Store. I also drew this infographic in the same app: https://mortaltree.blog/2017/01/06/ground-cover-infographic/ I’m keenly interested in Hart’s forest garden. From what I’ve gathered though, there’s little left of the original planting. See this post I wrote a couple years ago: https://mortaltree.blog/2014/02/02/robert-harts-forest-garden/ Let me know how it goes for you. Thanks for the follow too. I look forward to what we can discover together.

LikeLike

Soon you will transform Ohio into a global ecological destination! I ordered a bunch of siberian tree shrub seeds followed the instructions and froze them in dirt for a month and nothing happened. Tried it the other way and just planted them in pots and nothing happened. Sometimes it’s not worth trying to save a penny when you end up investing dollars in labor lol. Where can I get some Siberian Pea Shrub?

LikeLike

Really I’m just trying to help people realize what an amazing biological gem it is already. I tell my clients that the most rare rainforest in the world is the Appalachian rainforest. It’s a several hundred miles south, but I like to think I’m reminding the ecology here what it’s meant to be – a kind of “rainforest” being the goal. I’m designing a grotto for a client this year that has an especially tropicaleque feel with mimosa and Houttuynia cordata if I can source enough of it.

I’ve had equally poor success with Caragana. I gave the one prized specimen that lived to my mom as a gift. Check out Burnt Ridge: http://www.burntridgenursery.com/SIBERIAN-PEA-SHRUB-Caragana-arborescens/productinfo/NSSPSHR/ They sell them for very good prices in bulk.

As a note though, they grow very slow for me. I have some for diversity’s sake, and perhaps they’ll snap to it in a couple years, but I’m using Amorpha in it’s place. It’s so easy to start from seed.

I ordered a thousand bareroot plants of Lespedeza bicolor this year. If you’d like some let me know. I could spot you fifty or so as a gift.

LikeLike

In your post you mention a guild needs “at least 2 woody nitrogen fixing plants,” and it got me wondering why woody N-fixers would be preferable to forbs that do the same. I have a couple of guesses – perhaps it’s because they’re longer-lived and hold their position better through winter? Or maybe that you want to maximize the usefulness of your forbs by being able to chop and drop them, so you give the nitrogen-fixing task to woody plants because they don’t have chop & drop value that would have to be sacrificed?

LikeLike

You’re right that I prefer chop & drop from taller plants and to leave the forbs generally for ground cover, yes. Very insightful. It’s also a matter of quantity of N needed for a given guild. I have exact calculation from Martin Crawford for which species of tree need how much N to fruit proficiently. Woody N fixers bring in more nitrogen for less effort than most lower forbs (generally speaking), by nature of the fast, tall growth (many of mine grow from the ground to 6 ft tall per year). Another reason for adding woody N fixers is the qualities of woody mulch over herbaceous. Wood has “lignified” or turned woody. So named because the wood contains lignin. The presence of lignin affects a very different fauna of fungi rather than predominant bacteria in the soil. The results is a soil fertility with longer lasting, more stable character, and a higher cation exchange capacity than would be gained with herbaceous plants as the source of N -fertility is of course more than just the value of N on a lab analysis haha. I hope this helps satisfy your query, Emily.

LikeLike

It does, thank you for sharing! Very useful to know.

LikeLike